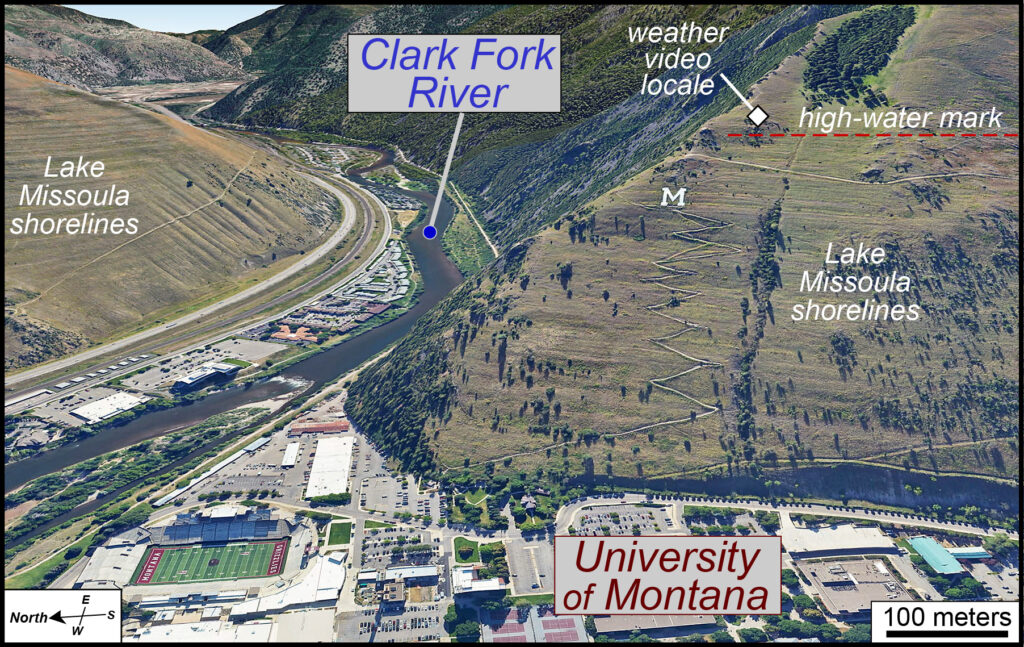

Missoula, Montana is a college town built on the flat ground flanking the Clark Fork River as it emerges from the Garnet Range and John Long Mountains. In March 2024, I was in Missoula visiting Mountain Press Publishing and its owner John Rimel suggested I hike up University Mountain for a visit to the big M that is shellacked onto the mountainside.

An oblique view of the Big M above the University of Montana (view is to the east). Imagery from Google Earth.Early the next morning I awoke ready to hike, but Missoula was socked in with fog. Nevertheless, off I went. From the valley floor, I climbed up ~200 m (600’) along a set of switchbacks to reach the big M that was very much in a cloud. So, I climbed higher, eventually popping out into a brilliant early spring morning.

Here’s the weather video from my vantage point above Missoula.

There is calm in this video with almost no wind and sublime conditions. I’m above a stratus cloud that reaches to ground level (that’s fog). There is also a second deck of stratus clouds to the north and east, these clouds are starting to break apart and dissipate.

The lower cloud, which I had just walked through, developed over night as colder air in the mountains flowed down slope – cold air is denser than warm air, and gravity abides. The cold air piled up, crept across Missoula, and ultimately reached its dewpoint temperature during the night. And, viola! The air was saturated with the water vapor condensing into tiny droplets, and fog was upon the fair city.

If you like stories about clouds, that’s a reasonably good one. But wait there is more!

Lens flare when the camera is pointed towards the sun.This video has some visually exciting shenanigans. For example, the lens flare as the camera pointed towards the east/the sun (25 to 30 seconds into the video) when light was recklessly scattered through the camera lens.

At about 50 seconds into the video, with the camera panning to the west, there is a curious circular halo at the top of the stratus cloud below me. In the still image, the halo’s got a rainbow-like quality and at the center of that halo is me! Actually, it’s my shadow projected onto the top of the cloud. It looks like a sundog, but this image is at opposition to the sun.

Still images of an anthelion, a birefringent halo. I'm the shadow at the center of the halo.Sundogs are halo-like rings with the sun at the center and created by light refracting through ice crystals in high elevation clouds. This halo is a curious phenomenon known as an anthelion. I’d seen these features a few times before while peering out airplane windows during descents towards a cloud deck (these features are also called aviators’ halos). Yet, I’d never personally been the center of an anthelion rainbow.

But there’s even more to this video!!

The top of that fog layer, parked above Missoula, was more-or-less at the elevation of the high-water mark for Glacial Lake Missoula. The top of the cloud, at ~1,300 m (~4,200’), is the same level as the waters of Glacial Lake Missoula some 15,000-years ago.

Still image of the video looking towards the south-southwest. The top of the cloud is at the elevation of Glacial Lake Missoula.I was gazing out at a scene from the Pleistocene. Time travel before breakfast.

A trail marker denoting the high-water mark of Glacial Lake Missoula.Lake Missoula was a massive proglacial lake that existed in what is today western Montana and northern Idaho. During the Last Glacial Maximum, when the Cordilleran Ice Sheet extended its ponderous glacial fingers (or lobes) southward, the Purcell lobe flowed into the Clark Fork valley effectively damming up the river behind a wall of ice. Upstream from the ice dam Lake Missoula developed, flooding the landscape and covering a vast area (2,750 km2). In places, Lake Missoula was more than 600 m (2000’) deep, storing an amount of water equal to the combined volumes of present-day Lake Erie and Ontario. It was a big lake.

Simplified map of Lake Missoula, the Scablands and the temporary lakes alongside the margin of the Cordilleran ice sheet. From Waltham (2010).Big lakes have big waves that slosh water about all along the shoreline creating havoc and in the process erosion-carved shorelines. The Lake Missoula shorelines are little notches evident in hillslopes across western Montana. There are dozens of old shorelines preserved on the slopes above Missoula.

But what happened to Lake Missoula?

Glacial Lake Missoula was rapidly drained by multiple catastrophic floods as the ice dam was breached. With each breach, epic volumes of water were released as the proglacial lake rapidly drained. When the ice dam broke, peak discharges exceeded 350 million cubic feet per second (10 million m3/sec) – that’s way more discharge than any modern river flushes out (Amazon, Ganges, Congo, and all the rest). Downstream these ‘Missoula’ floods created the Scablands of eastern Washington, colossal ‘fluvial’ landforms whose scale is difficult to grasp for mortal geoscientists.

The catastrophic flood(s) model for the formation of the Scablands was anathema to early- to mid-20th Century geologists besotted by Uniformitarianism. For decades academic battles full of venom were waged over the landscape origin in this corner of North America. Ultimately, the geoscience community recognized the catastrophic origin of the Scablands.

And, for a moment of time on the at spring morning, I was privileged to stand on a mountain looking down at a blanket of cloud, a cloud with footprint similar to Glacial Lake Missoula. Lake Missoula may be long gone, but its legacy is etched on the landscape.

Further Reading on Glacial Lake Missoula

Waltham, T., 2010, Lake Missoula and the Scablands, Washington, USA. Geology Today, v. 26, n. 4, pg. 152-158. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2451.2010.00763.x

Alt, D., 2001, Glacial Lake Missoula and its humongous floods. Mountain Press: Missoula, 200 pp.

I really enjoyed learning about the Stratus clouds and how they are made. I also loved the picture showing the Anthelion, which is a birefringent halo. I thoroughly enjoyed seeing the pictures of the beautiful Montana landscape and how much it differs from Virginia’s landscape!

This anthelion is so interesting and ethereal. What a lovely hike experience documented in the video! Thanks for sharing. I am thinking: Are the scablands essentially canyons but carved much more rapidly than others (i.e. the Grand Canyon)?