Tonight, 56 years ago, on August 19th to 20th 1969, the remnants of Hurricane Camille deluged Nelson County, Virginia and in the process supercharged the Tye River with high flows and flooding that had never before witnessed. Across the Blue Ridge foothills more than 30 cm (12”) of rainfall fell in 8 hours with some locations receiving in excess of 75 cm (29”). The intense precipitation spawned thousands of landslides, primarily debris flows in the steep uplands, and epic flooding downstream in valleys. 124 people were killed in Nelson County – 1% percent of the rural county’s total population.

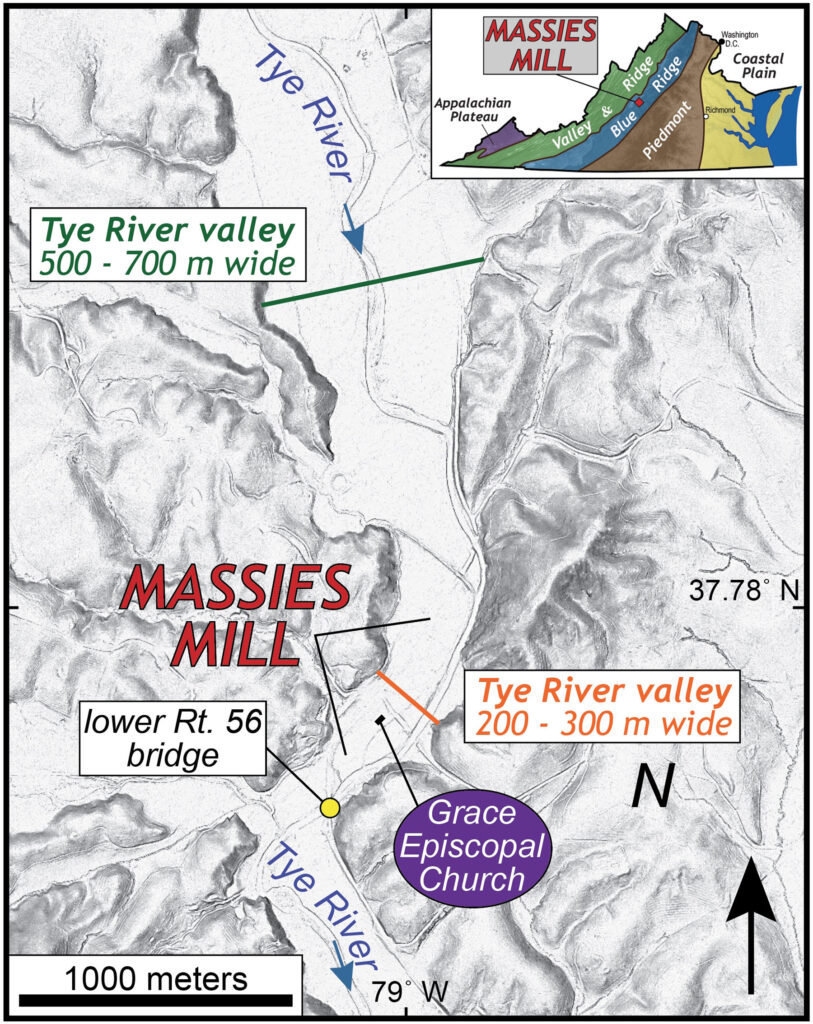

Shaded relief map of the Massies Mill area, Nelson County, Virginia.Massies Mill is a small village along the Tye River, and as its name suggests the community got its start as a mill town; at various times it supported both a gristmill and a sawmill. In the early 20th century Massies Mill was a prosperous community with hundreds of residents while it served as the terminus of the Virginia Blue Ridge Railway, a short line railroad that hauled timber from the highlands. By the summer of ‘69, both the mills and the railroad were gone yet ~100 residents still called Massies Mill home.

Early 20th century image of Massies Mill (view to the north) from Andy Keller's Family History BlogIn the wee hours of August 20th, after hours of rain with a constant drumbeat of thunder and strobe-light lightning, the normally modest Tye River became a torrent. Twenty-two people perished in Massies Mill that night, and the stories of that trauma are utterly gut wrenching.

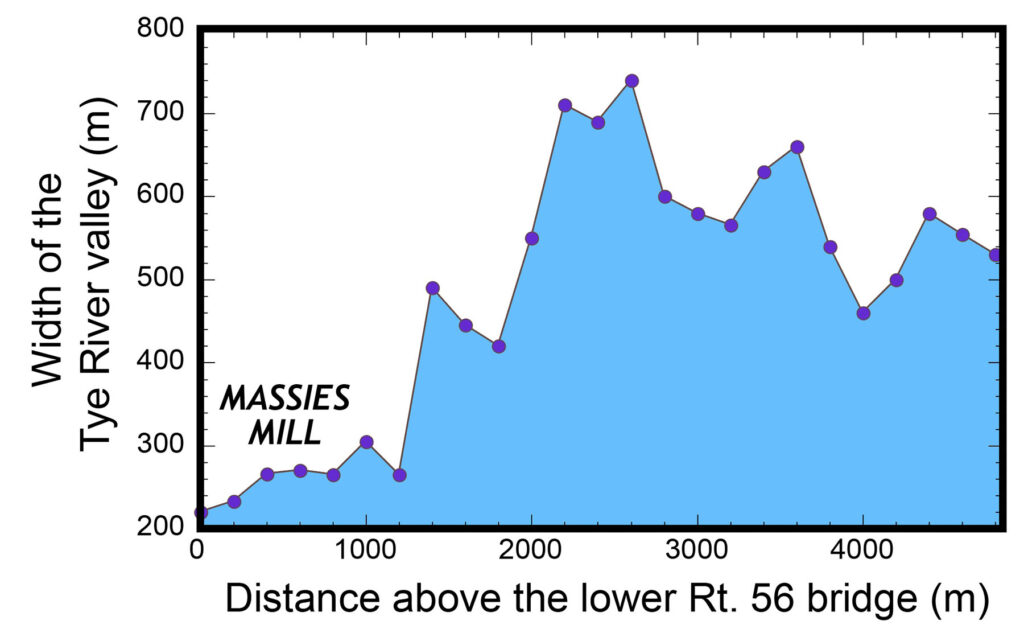

As the Tye River exits the Blue Ridge Mountains and flows into the foothills, the width of the its alluvial valley ranges from 500 to 700 m wide. But that valley width abruptly changes as the Tye arrives at Massies Mill, narrowing to somewhere between 200 and 300 m. During the Camille flood, the Tye River’s flow far exceeded bankfull discharge, and in many places the flood covered all of the Tye River bottomland.

Width of the Tye River Valley (at 5 meters above the channel bottom), derived from LiDAR elevation data. The Tye River valley is considerably more narrow in Massies Mill than it is upstream.What happens to the height of a flood’s flow as a valley’s width narrows?

The narrowing of the Tye River valley at Massies Mill is significant, as this constriction – a narrower valley, means that flood waters are higher and likely also flowing with greater speed than upstream where the valley is broader.

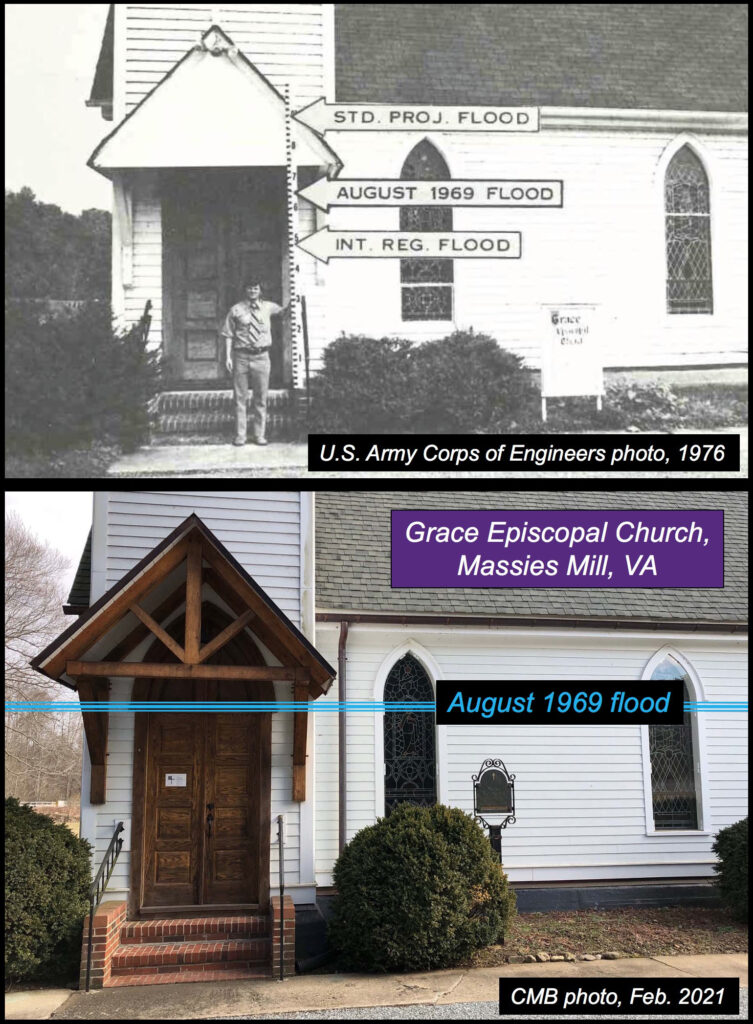

Just how high was the flow was as Camille’s floodwaters rolled into Massies Mill? At the Grace Episcopal Church, the flood blew out windows and left stains/watermarks both inside and outside the building indicating that the water was nearly 3 m (9’) high on the structure.

Two images, from decades apart, of the western entrance to the Grace Episcopal Church in Massies Mill illustrating the flood height from August 1969. In the upper image note the fashionable 1970s vintage tie (or is that tye?:) on the hard-working geoscientist. So, how fast was the water flowing as it coursed through Massies Mill?

Trust me, even 56 years later, we can estimate a reasonable answer to this question.

Let’s start with the concept of stream discharge – the volume of flow per unit time. In the United States, we typically measure flow in cubic feet per second (cfs), and in spite of my desire to go with SI units, we’ll stick with cfs for this exercise.

Discharge (ft3/sec) = area of the channel (ft2) x average flow velocity (ft/sec)

At a bridge just downstream from Massies Mill, geoscientists working soon after Camille estimated the highest flow during the flood to be a whopping ~65,000 cfs. For perspective, the yearly average flow on the Tye River is ~100 cfs while the highest flows over the past 20 years have topped out at ~7,000 cfs.

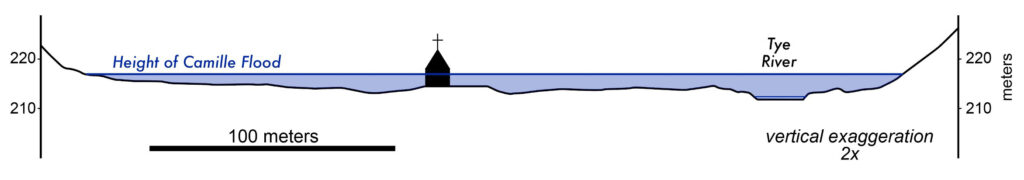

The highwater mark at Grace Episcopal Church is important because when that observation is combined with a detailed topographic cross section (obtained from LiDAR data) the area of the channel at peak flow is known and it’s ~9,800 ft2.

LiDAR derived elevation profile across Massies Mill illustrating the height of the Camille flood. Grace Episcopal Church is rather evident in the cross section.Now we rearrange the equation to solve for discharge

Average flow velocity (ft/sec) = 65,000 cfs / 9,800 ft2

Yielding an average flow velocity of 6.6 ft/sec or 4.5 miles per hour.

From personal experience, gleaned while cavorting in my favorite Tye River swimming hole (with its ~6’ of depth and a flow of ~1’/sec), I can dutifully report that it’s impossible to stand up much less stay in one place while in mid-stream with that flow. Amp up the flow to 6.6 ft/sec and one would be washed downstream in a terrible flourish.

Grace Episcopal Church mostly likely survived the deluge because half-a-dozen trees on upstream side of the church caught significant flood debris. However, most buildings in Massies Mills weren’t that fortunate. Many houses were lifted off foundations and floated, intact or otherwise, downstream coming to rest against other structures and debris. Nearly all of the survivors from that awful night in Massies Mill endured while trapped inside buildings. Those that went into the water were done for.

Oblique aerial view of central Massies Mill after the Camille flood in August 1969. Grace Episcopal Church is in the upleft left corner. Note the flow path is evident and some buildings are gone, washed off their foundations. Structures to the right were flooded but survived. Photo from the Library of Virginia collection.In 2025, Massies Mill has far more kudzu than residents. Grace Episcopal Church still stands and does important work for its community. Yet here, and in Nelson County, and all across America, so many homes and our built infrastructure reside on floodplains that are not frequently inundated. But in our changing world, where ‘never before’ floods are becoming the new normal these structures are in harm’s way and more tragedies like Camille are yet to come.

_______________________________________________________________________________

p.s.1 – unfortunately, this post did not drop before the end of Tuesday (August 19th, 2025- EDT), a.k.a. Tye River Tuesday, but it’s still in the window of the Camille deluge and that terrible tragedy from 56 years ago.

p.s.2 – in my 1st-year writing class in college (Fall 1985), I applied my burgeoning interest in geoscience to craft a paper about the Camille floods and Massies Mill. That was 40 years ago and I earned a solid B for that effort. It remains to be seen how the 2025 version of this tale will be judged :).

FURTHER READING ABOUT CAMILLE’S IMPACT IN NELSON COUNTY

Wow, found it interesting that the Tye River’s narrowing at Massies Mill made the floodwaters rise even higher. Such a small detail but with a huge consequence.

Within the community of Massies Mill many structures were totally obliterated, several were ripped apart with portions still standing and a number of others floated off their foundations coming to rest, still in tact, at a new location. Oral histories and post event photography have documented that some transported structures and debris, sheltered some downstream homes and buildings. This suggests the water depth and velocity varied in isolated locations, thereby saving some lives and structures. Not an ideal refuge, but one that was greatly appreciated by a few.

This information is interesting especially when concerning how floods repeat themselves. The Flood that occurred in Massies Mill was pretty significant and caused great damage. It was highlighted later on in the article that the Tye River has become ever narrower which means that if floods do occur now the damage can be even more destructive. I think this article put into perspective how time can change the environment which impact ways of life. I believe it was very cool that even with the flood the church was able to withstand and not gain much damage!