James Monroe was America’s 5th president and at the beginning of the 19th century he called Highland, an antebellum plantation in Virginia’s Blue Ridge foothills, home. In 1825, saddled by personal debt, Monroe sold the Highland estate and over the intervening two centuries, the plantation has had a numerous owners. Fifty years ago, philanthropist Jay Winston John’s willed the property to William & Mary. Today, the 500-acre property is a historic site, a working farm, and a W&M campus that’s ideal for place-based learning and research. In 2022, I commenced research at Highland to understand the landscape and link deep time to both the historical and ongoing land use at Highland.

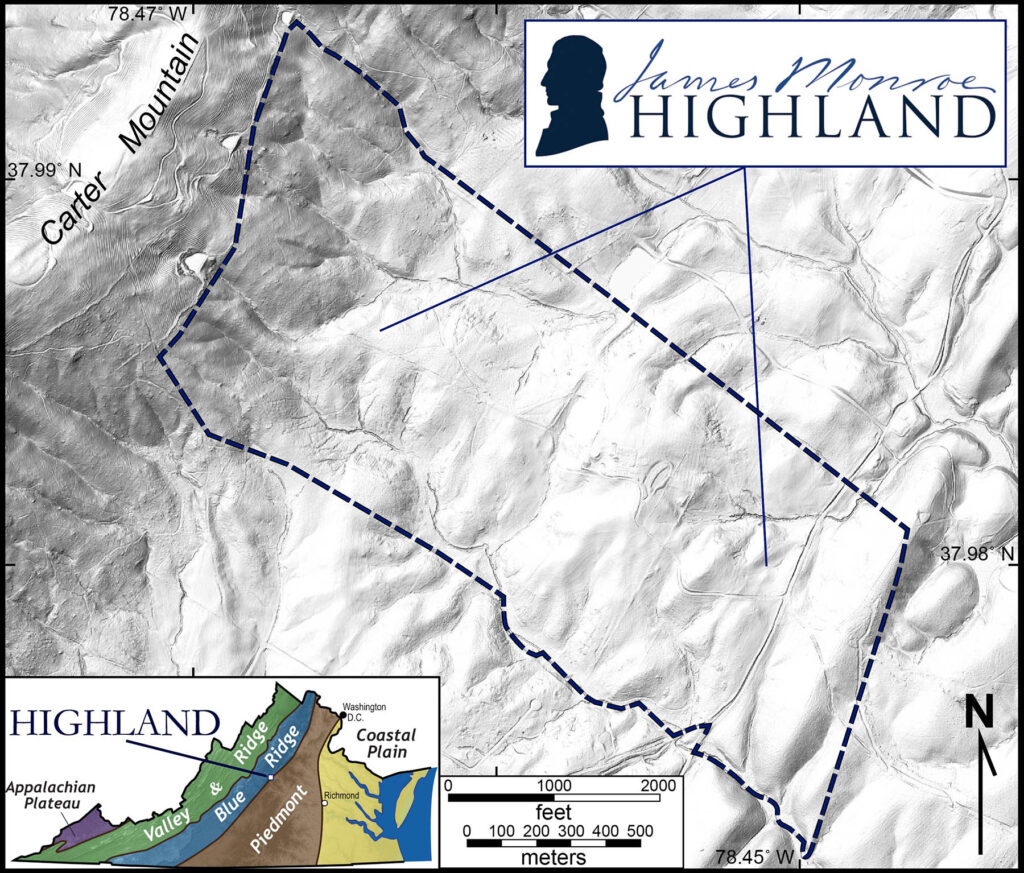

James Monroe’s Highland plantation on a shaded relief LiDAR map.During the winter and early spring of 2022, students in my Field Methods course undertook a semester-long project to study the bedrock geology, geomorphology, and landscape history at Highland. This was followed by Morgan Sanders’ senior research project.

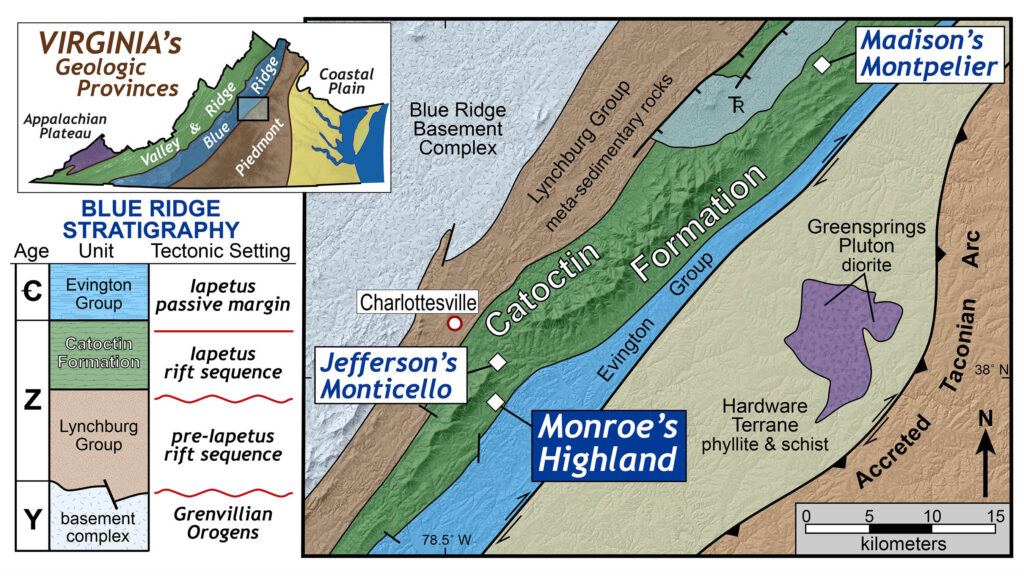

The 2022 William & Mary Geological Field Methods class at Highland.The geology at Highland falls short of spectacular. The property is primarily underlain by meta-basaltic greenstone of the Catoctin Formation, however outcrops are few and far between, as the landscape is typically covered by a distinctive reddish soil. These ultisols are flush with base cations yielding highly fertile silty loams. It’s no accident that three America Presidents had large plantations sited on the Catoctin Formation rather than on the poor soils (from an agricultural perspective) which form on the ubiquitous phyllites and schists of the Piedmont.

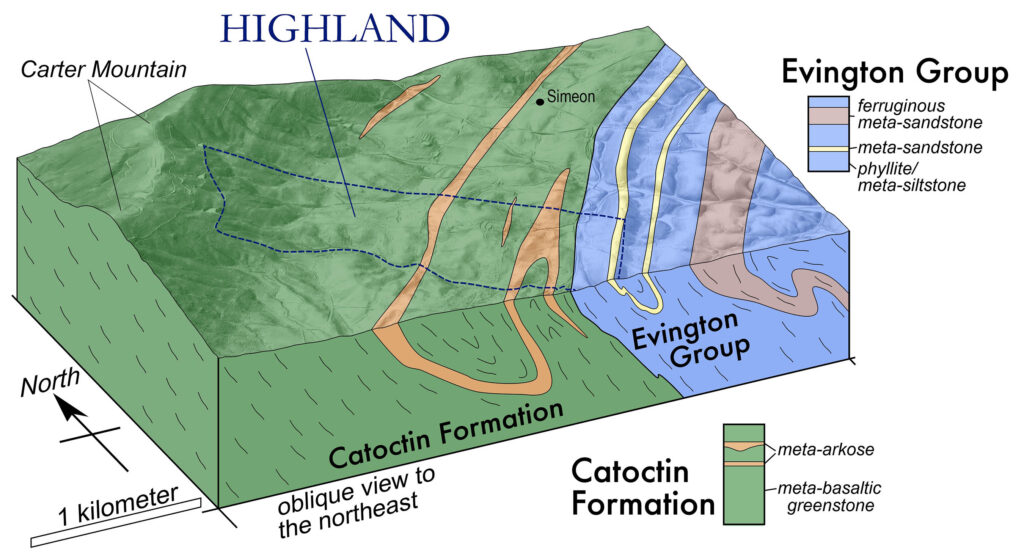

Overview geologic map illustrating the location of presidential homes/plantations in central Virginia, all of which are sited on the Catoctin Formation.Our research led to a detailed new geologic map of Highland and the surrounding terrain. During the Ediacaran (550 to 570 million years ago), the Catoctin basalts flooded a barren landscape and were the harbinger of a new ocean basin – the Iapetus Ocean. In central Virginia, the pillow lavas and breccias at the top of the Catoctin Formation provide the critical evidence of Iapetus’ watery advance across ancient Virginia.

Geologic map and 3D block diagram of Highland.

Hand sample of meta-arkose from Highland.Yet, it’s not all greenstone at Highland – interlayered within the meta-basalt are sheets of metamorphosed arkosic sandstone and siltstone. These fluvial deposits are derived from the erosion of Grenvillian granitic rocks exposed in a long-ago vanquished highland to the west. The stratigraphy hints at the dynamic interplay between rifting, sedimentation, and volcanism.

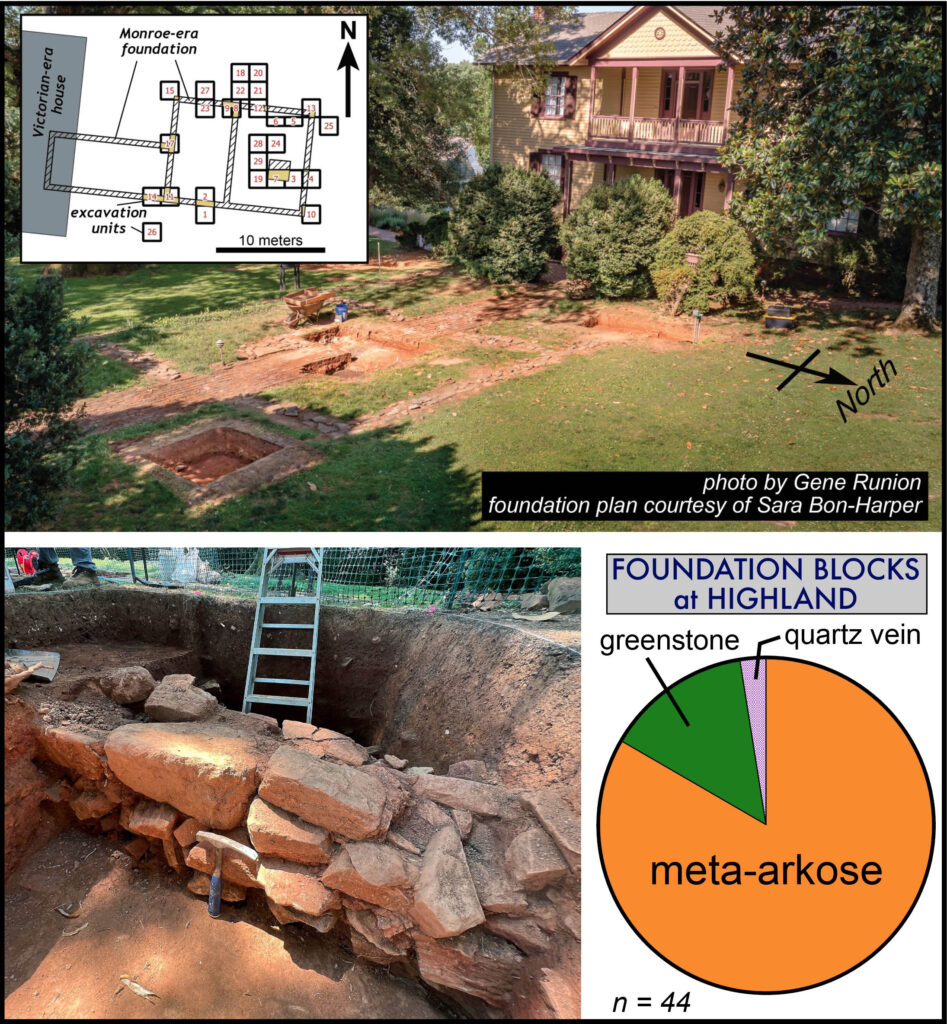

In contrast to George Washington’s Mount Vernon or Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello, Highland is a different kind of historic destination as there is no big house of the ‘great’ man to be seen or toured. For years there was controversy about the lack of the big house at Highland. After Monroe sold the property a later owner constructed the still standing Victorian-era farmhouse and there’s a modest guest house dating from Monroe’s time. To the casual visitor, Highland seems a confusing mishmash of multi-era architecture.

But in 2016, archaeologist Dr. Sara Bon-Harper (Highland’s Executive Director) and her team discovered the foundation of Monroe’s original house built in 1799. The foundation of that structure endures, a foot or two below the surface, in the front yard of the Victorian-era farmhouse. We now know that a fire destroyed the original house. What remains of Monroe’s house is primarily its stone foundation and much of that foundation is meta-arkose, locally-derived arkose. The arkose’s tendency to form rectangular blocks- bound by joint and vein sets, makes it well-suited for foundation stone.

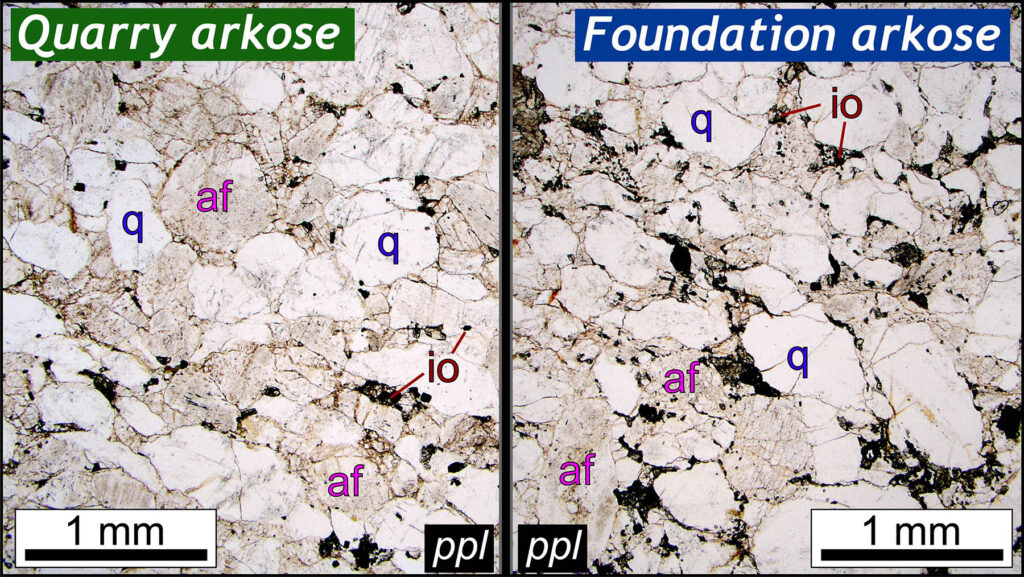

Top- view of part of the footprint for the 1799 Monroe house and the foundation plan. Lower Left- in-situ foundation stones exhumed in a 2024 excavation. Lower Right- pie chart illustrating the abundance of meta-arkose blocks (~80%) in the structure’s foundation.Hidden in a grove of red cedars, just a few hundred meters from the foundation of Monroe’s long-gone house, we discovered the remnants of a quarry cut into a regularly jointed, but massive meta-arkose. Morgan’s petrographic analysis of samples from both the foundation and the old quarry reveal these rocks are texturally and mineralogically identical. It’s exciting to have located the source of the foundation stone as there is joy in discovery and, in this case, connecting deep time to the early days of the American Republic.

A quarried block of meta-arkose at the quarry site ~200 m east of the foundation of Monroe’s 1799 house. The block is bound by subparallel joints/veins.

Micrograph of meta-arkose from the Highland quarry site and the foundation stone – they are the same stone. af- alkali feldspar, io- iron oxide minerals, q- quartz.Here’s a toolmark cut into the meta-arkose during the quarrying of that stone.

Tool marks in a meta-arkose block.Whose labor created that toolmark? Who quarried these stones and transported those blocks to the house site?

James Monroe’s work at Highland was done by enslaved people, and that’s a big part of the story at 18th and 19th century sites across the southern United States.

In their song Wildfire, the duo formerly known as Mandolin Orange (nowadays Watchhouse) reflect on American history from the American Revolution to the Civil War,

From the ashes grew sweet liberty

Like the seeds of the pines when the forest burns

They open up to grow and burn again

And it should’ve been different, it could have been easy

But too much money rolled in to ever end slavery

And the cry for war spread like wildfire

And it should’ve been different, it could have been easy… to my way of thinking, it’s a sentiment that resonates today as we collectively reckon with our nation’s history. Subjugation and freedom, prosperity and poverty – geology has played its role in this dichotomy throughout history.

_______________________________________________________________________

This post is drawn from a talk I gave at Highland on September 6th as part of the 50th anniversary celebration of William & Mary’s stewardship at Highland. More talks are to come later this fall. Check out that calendar here- https://highland.org/highland-celebrates-50-years-of-william-mary-ownership/

I also discussed our research at Highland during my 2023 Geological Society of America Presidential Address – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T-MfU2vjLYQ